UNV was established in 1970 and deployed the first volunteers one year later. An international UN Volunteer of the first hour, Jerome Montague (USA), takes us back on a journey that started in 1978 in Papua New Guinea and shares insights on how volunteerism influenced his career in the years to come. Already in those days, UNV deployed its volunteers amongst communities. For Jerome Montague that did not only mean to be in the field, it literally meant to be in the swamps: Jerome served with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as a Wildlife Officer in Lake Murray, providing assistance to the crocodile skin industry at the Baboa crocodile station.

UNV and the crocodile skin industry? This surely was different from what most UNV assignments revolved around. Jerome Montague’s description of assignment reads as follows:

To fully understand what this assignment is about, one must look at the bigger picture. Papua New Guinea achieved independence from Australia in 1975 and was needed to establish its own economy.

By turning crocodile hunting into a crocodile farming industry, the government offered opportunities of economic improvement for people in the most rural areas, at the same time that it improved the health of wild crocodile populations.

But since crocodile skins, a luxury item, was one of the few items of commercial value to rural people, crocodile overhunting has become a serious issue. The assignment aimed at creating an economic incentive for local villagers in order to protect wildlife and maintain renewable resources.

The first thing we did, was to make it illegal to sell the skin of a crocodile that was big enough to be a breeder. People were encouraged not to kill small crocodiles for their skin but rather capture them alive and sell them to the government for a higher price, where they then would be raised into a larger more valuable skin. --Jerome Montague, former UN Volunteer Wildlife Officer with FAO

"Most of the people in the area I was deployed in, had no monetary income. They lived off the land as hunters and gatherers. This is where game ranching comes into play. It is a concept of wildlife preservation, where you try to conserve natural areas by showing that you can make more money by harvesting fish and wildlife and native plants than you could by harvesting crops and animals," Jerome Montague explains.

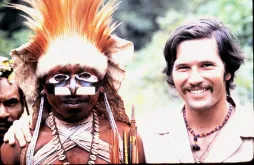

By doing so, Jerome was in regular contact with local villagers and indigenous people who inhabited Lake Murray such as the Kuni, Biami and Pari. He developed a deep comprehension of their lifestyle, including, for example, the concept of how non-verbal communication could go a long way when one was overwhelmed by the more than 800 spoken languages in Papua New Guinea.

Working so closely with indigenous people at Lake Murray shaped his life quite far beyond the actual UN Volunteer assignment. Jerome subsequently finished his PhD degree in Wildlife Ecology at Michigan State University, and moved on to become the manager of a crocodile farm outside of Darwin, Australia, where he was working with Aborigines.

His next job brought him from the Australian bush to the Alaskan pack ice, where he was doing research on the bowhead whale. This put him in the position of an intermediary between offshore oil development agencies, who were looking for places to drill oil and the native Iñupiat, whose culture centered around the bowhead whale, which was at home in this area.

"When I worked with native people elsewhere, even though they weren’t for the most part living a true hunter-gatherer lifestyle like the New Guineans were, I understood where they came from and what their perspective was in a way that someone who hasn’t had that experience could never do," he says with hindsight of advocating for the Iñupiat's interests.

My experience in Papua New Guinea was extremely beneficial, because I was working with people in what you would term 'first contact'. All the rest of my career, I have been working with native people who have been in contact with Western, literate technological cultures for at least one generation and often five or six. --Jerome Montague

In his following job position as a director of the oil spill division at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, he dealt with the aftermath of the Exxon Valdez Oil Spill, which destroyed over 1,300 miles of coastline in 1989.

Not only did this affect the ocean and its animals, but also the indigenous people, called Alaska Natives, who inhabited most of the affected land. By researching the impacts of the oil spill and later restoring the damages of the fish and wildlife, he has – just like in his job before – worked closely with indigenous people.

This is the career path of a UN Volunteer, who chose to be an intermediary between indigenous cultures and the modern world and to connect both its people through scientific research, cultural sensitivity and the ability to apply acquired skills, be it in the tropical swamps of Papua New Guinea or in the Polar pack ice.

My two years in Papua New Guinea were really – in terms of enjoyable, challenging and eye-opening experiences – the best of my whole career. --Jerome Montague

This retro perspective on volunteering with UNV shows one thing above all: the gained comprehension of life conditions different to one’s own, will accompany you far beyond the end of your volunteer assignment.

Interested in what working at the Baboa crocodile station looked like? Zoologist Marlin Perkins visited Jerome Montague for his famous TV documentary Wild Kingdom. Check it out.

This article was prepared with the kind assistance of Kim Nienau.