Océane Musaniwabo Mlanao doesn’t just talk about human rights—she walks straight into prisons to advocate for them. Based in Phnom Penh, she is a UN Volunteer Associate Human Rights Officer with the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and spends her days face-to-face with detainees, listening to their stories and documenting their experiences. Océane is from France and her assignment is funded by her home country.

Every day at the office looks different for Océane. Some days, she travels to a detention center outside Phnom Penh to meet with a detainee. On other days, she attends a trial. But her focus is always on delivering recommendations that improve prison conditions and the treatment of prisoners through legal reform.

Prisons are overcrowded in Cambodia and detainees may face challenges in accessing justice. Most of the detainees have been convicted of drug-related offenses. Océane visits these detention centers alongside Cambodian colleagues, who assist with translation and provide cultural context. She interviews detainees, always obtaining consent, and documents conditions such as food allocations, sleeping space, and treatment under custody. These detailed reports create the basis for recommendations to the local prison management.

Océane’s day-to-day work is not without challenges. Language barriers make the work a tad difficult since English is less commonly used outside the office. Plus, it's her first time living and working in Southeast Asia, and she admits the unfamiliarity has been a learning experience. “It's my first time on the Asian continent, and also in Southeast Asia. I did not really know the context, so it’s new for me to understand the dynamic and the background of the country.”

She continues, “The topic I'm working on requires a lot of diplomacy with the institution, because we are talking about something related to the order of the state, the sovereignty. So, it might be a bit tricky at times to talk about the condition of detention, the over-incarceration and the advocacy for less incarceration. But I think the more I conduct these interviews, it helps [me] be closer to the people in need.”

Océane feels grateful for the French Government's funding because it empowers her to make a real impact through her UN Volunteer assignment—and keeps her work going strong despite UN budget cuts. “[Volunteering] can be a way for us to demonstrate to France that their money is well spent, highlighting that what we do is bearing result.”

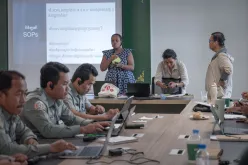

Océane took on a pilot project—shining a light on life inside an overcrowded prison. By listening to inmates, staff, and health workers, she’s breaking down walls—bringing government officials and NGOs together to address the facts and suggest solutions. “I drafted a note, which helped us organize a stakeholder meeting that gathered 100 participants from ministries, including the Directorate General of Prisons. Here we exchanged and defined some recommendations for an improvement of the detention conditions.”

While change takes time, this project is a hopeful start toward a more just system. No stranger to development work, Océane reflects that, so far, her experience as a UN Volunteer has been different from other missions, and she appreciates the autonomy she is afforded to do her job. She accepts that at times, development organizations can be critiqued, but encourages people to look at things differently.

“I always say that you can help by doing small steps—it can be frustrating because we’re not changing the world. But at least when you work as a UN Volunteer in the field, you can take those small steps.”

There is also the profound personal shift that occurs with volunteering. Océane highlights how her time in Cambodia is broadening her worldview. “[Volunteering] helps you to develop a sense of understanding, diplomacy and adaptability, meaning that you’re allowing yourself to understand others, but also not to think that your truth is the only truth.”

She sees volunteering as a two-way street and says it’s not about changing the world in an instant; rather, contributing little by little. "Volunteering is like a bridge and we're all in this together for global development.”

Océane’s assignment will wrap up in October 2026. She hopes that the pilot project will keep going strong—even without her boots on the ground. Through every challenge, one thing stands out: Solidarity.

“Cambodia is very open. People are really generous and kind,” she says. That spirit of unity is what keeps her going—and what she hopes will carry the work forward.

For more information about UN Volunteer assignments, click here. To read our stories, click here.