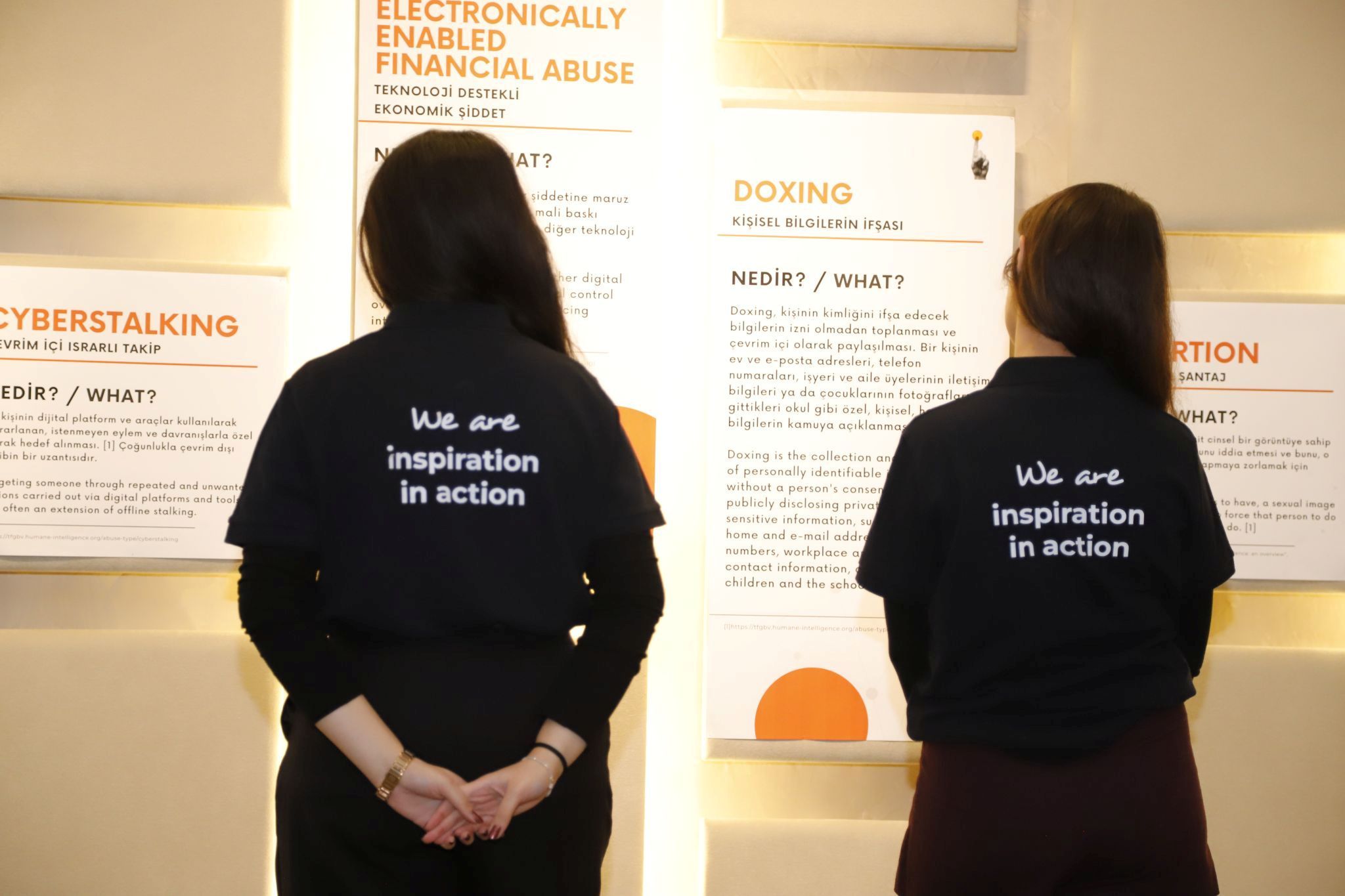

Digital violence is often invisible—but its harm is very real. UN Volunteer Communication and Advocacy Assistant and lawyer, Aslı Akbay Alagöz, breaks down victims’ rights under Turkish law and how to seek help. She is currently supporting the 16 Days of Activism campaign in her volunteer role with UN Women.

Aslı highlights Digital violence is real 'Dijital şiddet gerçektir' in her interview, originally published in Milliyet, a Turkish newspaper and Media Compact partner of UN Women Türkiye.

Aslı Akbay Alagöz explains the legal rights available to victims and stresses that women must be protected in digital spaces just as they are in the physical world. As the digital environment becomes central to daily life, the forms of violence have also evolved. Today, threats, harassment, stalking, the disclosure of intimate images, deepfakes, and AI-based manipulations are among the most common examples of digital violence. Aslı answers questions on the legal framework of digital violence and the rights of victims.

Cybercrime

■ How is digital violence defined under Turkish law? Which offences does it fall under?

Digital violence does not yet have an explicit definition in legislation. In academic literature, it is described as actions carried out through information systems to harm, disturb, exert pressure on, or control individuals. Although there is no direct definition, digital violence is assessed under offences regulated in the Turkish Penal Code such as sexual harassment, threats, blackmail, hate and discrimination, disturbing a person’s peace and tranquillity, stalking, insult, obscenity, violation of privacy, and cybercrimes.

■ Where should victims of digital violence apply? What should they pay attention to when collecting evidence?

It is essential to understand that digital violence is a real form of violence and that victims are legally protected. Victims may file complaints with the Public Prosecutor’s Office or police units. Under Law No. 6284, family courts, law enforcement, or local administrative authorities may issue protective and preventive measures. For content removal and access blocking, applications may be made to the IT Authority (BTK), criminal judgeships of peace, or content/access providers under Law No. 5651. In cases of unlawful sharing of personal data, complaints can also be submitted to the Personal Data Protection Authority (KVKK). The most important point in evidence collection is preserving the originality of the data. Screenshots must show the URL, date, and time. Messaging records, emails, IP and log information should be kept. The Turkish Notaries Union’s e-Determination (e-Tespit) application is highly effective for establishing evidence. Unlawful methods must not be used when collecting evidence.

Similar to physical violence

■ Can a restraining order be issued for violence occurring in digital spaces?

Yes. The protective and preventive measures under Law No. 6284 also apply in cases of digital threats, harassment, or stalking. Digital violence falls within the same scope of protective measures as physical violence.

■ What are social media platforms’ obligations regarding content removal and user protection?

Under Law No. 5651, social media platforms are not required to pre-moderate content. However, they must remove unlawful content once notified. Platforms are also obliged to comply with court orders, protect children, publish transparency reports, and maintain advertising registries. Foreign platforms operating in Türkiye must appoint a local representative and respond to user applications within 48 hours. Failure to comply may result in liability for damages under the Turkish Code of Obligations (Law No. 6098).

Administrative fines

■ How is the unauthorized sharing of images, messages, or data evaluated under KVKK?

Images, messages, and similar content are considered personal data. Sharing, processing, or disseminating them without explicit consent is prohibited. Such acts may lead to administrative fines for data controllers.

■ How are deepfakes, digital stalking, and AI-generated content addressed in existing law?

Digital stalking is evaluated as a crime of persistent stalking under the Turkish Penal Code and Law No. 6284. Although there is no specific regulation for deepfakes or AI-generated content, such materials may constitute offences such as threats, blackmail, or violation of privacy. The fact that the content is fabricated does not prevent the formation of the crime. Victims also have the right to file claims for material and moral damages.

The original interview in Turkish can be found here.