Time flies! After more than thirty years of service, I have recently retired from the United Nations. Not something I could do easily, but there is a time for everything.

I joined the UN in 1992 as a UN Volunteer in Cambodia, just after the Cold War ended. A UN Transitional Authority was being set up in Cambodia, the largest UN endeavour since the UN operation in the Congo in the 60’s. Amidst 20,000 personnel, military and civilians, 465 UN Volunteers—including myself—were deployed as District Electoral Supervisors. Despite the Khmer Rouge boycotting the elections and the ongoing civil war, we organized elections in a Khmer Rouge-controlled area. I spent a year, from July 1992 to July 1993, in a Cambodian district, and supervised 300 Cambodians alongside a fellow volunteer from Korea. Little did I know, before I left for Phnom-Penh, how intensive, chaotic and unforgettable this experience would be!

On 8 April 1993, as the elections were getting closer, one of our fellow UN Volunteers, Atsuhito Nakata, from Japan, and a Cambodian interpreter working with him, Lek Sophiep, were tragically killed in an ambush in the province where I worked. Several UN Volunteers left the country; others carried on despite the circumstances. At some point, the operation, relying heavily on UN Volunteers to organize the elections in every district, appeared on the verge of collapse. Against all odds, the elections we helped organize, took place throughout the country.

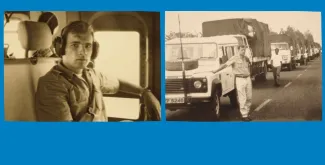

From Cambodia, I volunteered to serve in the former Yugoslavia with the UN Refugee Agency—UNHCR, at a time when humanitarian convoys were often caught in crossfire, and civilians were targeted. Based in Zagreb, I participated in a joint civilian-military coordination cell, being responsible for the preparation of airdrops and convoys of urgently needed humanitarian relief items.

Next, I worked as a short-term consultant for UN Volunteers in Geneva, heading a newly constituted Mozambique Task Force, to identify, train, equip, and deploy UN Volunteers to participate in the elections and demobilization processes in war-torn Mozambique. This being done, in April 1994, following the dramatic “Black Hawk Down” incident and the departure of US troops, I took off to Mogadishu, again as a UN Volunteer, to serve as a Policy and Planning Officer in the UN Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM).

While in Somalia, I was called by the Humanitarian Relief Unit of UNV headquarters, and asked to travel to Kigali, immediately after the genocide, being one of five UN Volunteers brought into the emergency relief effort of the UNHCR in Rwanda. We spearheaded the humanitarian effort, distributing blankets and soap to displaced Rwandans, as well as organizing the voluntary repatriation back to their villages of those who had fled to neighbouring countries and the so-called “Turquoise Zone”.

This incredibly intense chapter of my life was symbolically closed, in 1995, by an invitation to attend the ceremonies organized in London, at Westminster Hall and Buckingham Palace, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations.

This experience as a UN Volunteer was foundational, a baptism of fire, and a source of reflection. It inspired my PhD research on UN military forces, and was the beginning of a career under the UN flag.

Having witnessed the limitations of UN military forces in various theatres of operations, I completed and defended in 1999 a PhD thesis on the idea of a UN military force that would be directly recruited from volunteers. The idea had emerged cyclically since the creation of the organization, in conjunction with the successes and failures of the UN in keeping or making peace, and various attempts in availing its military force, since 1945.

After working at UNV headquarters to establish and manage UNV programmes in the Great Lakes region of Africa and in Kosovo* in 1998, I applied to UNDP’s Leadership Development Programme in 2000. Over the next 25 years with UNDP, this opportunity led me through a series of impactful assignments: supporting mine action in Angola, strengthening police capacity in Afghanistan, developing a post-electoral strategy in Haiti, coordinating early recovery efforts in Darfur, and advancing justice and livelihoods in Somaliland. My work also extended to supporting communities in Yemen, North Korea, and Chad. My final assignment before retirement brought me full circle—to Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country once torn by war.

Now it is time to look back! Retrospectively, what comes to mind is the omnipresence of risks. Had I not been a UN Volunteer in war-torn Cambodia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Somalia or Rwanda, I could perhaps never have operated effectively in other conflict situations and volatile environments. I had learned, inter alia, that risk can, and must, be effectively managed. This experience was a solid preparation for what was coming ahead.

Another important lesson I learned while being exposed to all kinds of hazards in the field is the importance of managing and pacing oneself. Certain situations, which may be a matter of life and death for others or oneself, require pushing one’s limits to the extreme, at times to the point of being on the verge of complete breakdown or collapse. It is all the more essential to periodically take a step back from work demands and continuously look after one’s health, both mental and physical, as well as dedicating energy to family and close ones, and developing a support network. We all have different thresholds to pain and hardship. Different people should not be expected to react the same way in every situation. Heroism has its limits!

Still, whether volunteer or staff, managing field realities while keeping faith in the UN mission requires a certain degree of selflessness and idealism, but also awareness. The UN itself, being a relatively new phenomenon in human history, is a work in progress. While one should not become cynical or harsh to oneself, one should not be naïve about it or get discouraged.

The UN may sometimes fail; and may even someday fall, if unable to reform itself; yet it will be replaced by a stronger, more effective organization, as the League of Nations was replaced by the UN. And what we have done, with all its limitations, but also successes, will thus be continued by others, one way or another.

With hindsight, would I do it again? Of course, differently, perhaps, but I would, without hesitation. To those who are currently in the field, I say: please continue the good work! The UN is the best travel agent in the world (when things would get tough in the field, I would sometimes tell my fellow workers: “Some people would pay to do what we get to do!”).

It is difficult to imagine the wealth of the relationships one can establish and maintain overtime, with people from all walks of way, cultures or origins while working for the UN, whether as a volunteer or a staff. The quality of the interactions you have with others while being confronted with inextricable dilemmas, literally participating in making history—is unique. The ultimate reward is making a difference in the life of people.

Beyond the extraordinary memories I carry with me, I consider myself as having been incredibly privileged, having acquired so many friends and worked in so many different places. Wherever I have been, I have left a bit of myself, and I have contributed to making the world a better place. I gained as much as I gave. This, in my view, is truly the true spirit of the UN, and, I believe, a hopefully a seed and promise of a better future for all.

In El Fasher, Darfur, on UN Day, 24 October 2011, delivering a speech on behalf of the UN Resident Coordinator.

____________________________________

[* All references to Kosovo mentioned here shall be understood to be in the context of United Nations Security Council resolution 1244]